Kanchenjunga, also spelled Kangchenjunga, is the third highest mountain in the world. The name Kanchenjunga, meaning 'The Five Treasures of the Great Snow', was always known by its original, local name. It rises with an elevation of 8,586 m (28,169 ft) in a section of the Himalayas called Kangchenjunga Himaldelimited in the west by the Tamur River, in the north by the Lhonak Chu and Jongsang La, and in the east by the Teesta River. It lies between India and Nepal. The peak of Kanchenjunga is a holy place, and by convention those who climb it stop short of desecrating its summit.

For me, it always reminds me of Darjeeling - the place Ma grew up. It is know for its distinctive “sleeping Shiva” silhouette as you can see from the photos from Das Studio below - we used to have one of these photos in our home:

***

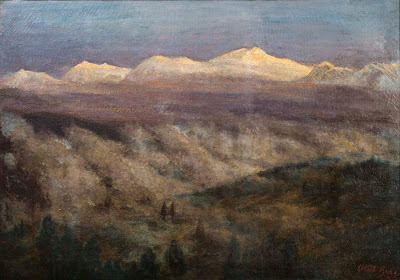

These are some of my favourite paintings of the famous mountain

J.P. Gangooly

Jamini Prokash Gangooly (1876-1953) belonged to the extended Tagore family in Calcutta. Like many of his class of affluent gentlemen artists, Gangooly didn’t go to art school but was a product of private art training at home, initiated later into art by Abanindranath Tagore. Gangooly painted at the time of rise of new nationalist and modernist art movements. The skills he commanded in illusionist oil painting, realist portraiture and landscapes were all part of the essential training that marked the formation of the new professional artist in colonial India. Over the first decades of the 20th century, Gangooly demonstrated his flair in various genres, ranging from portraiture to neo-classical and mythological paintings. However, landscapes and riverscapes became his chosen genre where he developed his special style of densely mist-laden atmospheric effects of sunrise and sunsets on bathing ghats, river banks and mountain ranges. Gangooly especially surpassed himself in the picturesque views of the Himalayas, and in the village and river scenes of Bengal. He painted nearly a hundred oils of the sun setting on the river Padma, which earned him the sobriquet ‘Painter of Padma’. In 1905, he was elected the joint chairperson of the Bangiya Kala Samsad, Calcutta, and founded the Indian Society of Oriental Art, Calcutta, in 1907. In 1936, he was elected joint director of the Academy of Fine Arts, Calcutta. Gangooly became vice-principal of the Government College of Art & Craft, Calcutta, in 1916, a position he held till his retirement in 1928.

"Kangchenjunga From Darjeeling" by J.P. Gangooly

"Sunset Kanchenjunga" by J.P. Gangooly

Oil on panel Signed to the lower left Titled and signed to the back 22 x 29 cm

Oil on board, Signed 'J.P. Gangooly' lower left, 11 ⅝ x 17 ¾ in. (29.5 x 45 cm.)

signed J. P. Gangooly' (lower left); further signed 'J. P. Gangooly' (on the reverse)

oil on board, 8 5/8 x 10¾ in. (21.9 x 27.3 cm.)

***

Atul Bose

“Kanchenjunga at Dawn” by Atul Bose (1936)

***

Nicholas Roerich

Among artists of the twentieth century Nicholas Roerich (1874–1947) stands out in many respects. He must be the only one who was nominated several times for the Nobel Peace Prize, and whose seven thousand paintings are among his lesser-known accomplishments. He was a polymath who trained first as a lawyer, but is much better-known for his spiritual philosophy and public profile. He painted prolifically throughout his adult life, and is generally accepted as being symbolist for much of that. Roerich was born and raised in Saint Petersburg, Russia, and trained simultaneously in law at the Saint Petersburg University, and at the Imperial Academy of Arts. He had settled in India by the outbreak of the Second World War, and lived its duration in his house in Himachal Pradesh, in the foothills of the Himalaya.

Roerich was clearly fascinated by the mountain Kanchenjunga, painting it nearly forty times over the course of his career, sometimes under the soft light of dawn or dusk, other times during the day. Each of these smaller scenes, however, depicts only limited portions of the Kanchenjunga range.

The subject of the Himalayan Mountain, which for the artist held a special spiritual significance as the holiest of places in the Eastern world, captivated Roerich throughout his career. While he began to paint various smaller versions of the mountain after his first expedition to the region in the 1920s, the present lot is the most spectacular monumental depiction of the legendary mountain range depicting the entirety of Kanchenjunga. All five sacred peaks of the renowned mountain float above blue clouds; their snow-covered summits juxtaposed against a spectacular magenta-coloured background. It is the culmination of Roerich's life's work on this theme, a true showcase of the artist's technical skill and a testament to his lifelong fascination with the mystery and spiritual significance of Kanchenjunga.

Kanchenjunga (1944) by Nicholas Roerich (1874–1947), tempera on canvas, 91.4 x 152 cm, Roerich Museum, Moscow, Russia. Roerich painted this superb view of the distant mountain Kanchenjunga in 1944, when he was living in India. This is the third highest mountain in the world, rising to 8,586 metres (28,169 feet), and wasn’t climbed until 1955. This view may have been painted in Darjeeling, and shows the mountain in the rich light of dusk.

Nikolai Roerich's Kanchenjunga, a remarkable painting executed in 1935-1936, is arguably the artist's most significant depiction of the legendary mountain Kanchenjunga ever to appear on the art market. In this particular version, listed as number '22' in a personal record of his work in 1935-1936, Roerich was able uniquely to showcase Kanchenjunga in its grandiose entirety: the only time he was able to do so in his career as an artist. Kanchenjunga therefore is a remarkable depiction of one of Roerich's favourite subjects, an extraordinary manifestation of the artist's technical virtuosity and his legendary spiritual pursuits.

Kanchenjunga captured the imagination of generations of Western explorers, travellers, mountaineers, and writers (Simon Pierse, Kanchenjunga: Imagining a Himalayan Mountain, University of Wales School of Art Press, 2005). In this monumental work, Roerich has imbued Kanchenjunga with all of the spiritual significance attributed to it by visitors and locals alike over the centuries. The pale peaks of the mountain range appear almost mirage-like, visually separated from their bases by hazy, lavender clouds. The mountain acquires an ethereal quality, existing not within the grounded earthly realm, but rather as an embodiment of an otherworldly, spiritual one. Roerich wrote reverentially of the mountain: "When we see a beautiful snow-covered peak, we are imbued with the spirit of a holiday, because the worship of beauty is the basis of this sublime feeling. The mountain settlers are able to feel the beauty. They experience the true pride of owning a unique snow-capped giant of the world, clouds, and fog monsoons. Is all of this not just a beautiful curtain covering the great mystery on the other side of Kanchenjunga? Many beautiful legends are associated with this mountain" (Nikolai Roerich, Source of Light. Treasures of the snow).

The name Kanchenjunga, meaning 'The Five Treasures of the Great Snow', was always known by its original, local name (Simon Pierse, op. cit.). For Roerich, the 'sacred mountain' held a particular spiritual significance. Gazing on its vista from his home in the Kulu Valley, the artist, spiritualist and philosopher believed that Kanchenjunga's great peaks held innumerable mystical secrets. It is therefore no coincidence that Roerich sought a home that allowed him to see such magnificent views of Kanchenjunga on a daily basis. Describing his arrival in Sikkim in 1923, he wrote: "We searched for a house...we wanted something further away...where all the Himalayas could be seen." Up until 1852 this five-peak mountain in the Sikkim Himalayas was considered to be the highest point in the world. Kanchenjunga was revered as a sacred space long before Western travellers first glimpsed its snowy peaks. It was believed to be an 'abode of God'; its white peaks, often obscured by clouds and mist, sometimes appeared to exist in a separate celestial realm, contributing to its allure as an otherworldly phenomenon. According to the pre-Buddhist beliefs of the people of Lepcha, the mountain Kanchenjunga was the origin of the people who first settled the Himalayas. Moreover, the mountain itself was sometimes believed to be a 'god' or 'demon', and the Hindu god Vishnu was thought to appear in the mountain in various incarnations (Simon Pierse, ibid.).

For Roerich, who believed that the Slavic and Indian cultures shared a common origin, Buddhist philosophy held a special spiritual significance. Roerich was particularly interested in the Shambala, which signified a mythical link between heaven and earth and which was thought to be located within a hidden valley deep in the Himalayas (Simon Pierse, ibid.). He wrote of Kanchenjunga, 'There is an entrance to the holy land of Shambala. Through the underground caves amongst astonishing ice caves, only the chosen few in this life reached the sacred place (Н.К.Рерих. Обитель Света. Сокровище снегов). Furthermore, Roerich believed that the sacred mountain was the source of the five spiritual treasures of the world, which would become available to humanity in the most difficult of times. He believed Kanchenjunga would sustain mankind through a spiritual famine, writing: 'He who comes from Kanchenjunga will nourish humanity, not physically, but spiritually' (Ibid, p. 247-248).

.jpeg)

.jpg)